Marconi Towers from path. Photo given to me by Ed Ayres. Possible F.C. Hicks photo

Early in 1904, Mr. Paget and Mr. Taylor — Marconi engineers — came to South Wellfleet to prepare the Marconi station to become part of the company’s service of press and

private messages for subscribing ships at sea on the transatlantic route. The South Wellfleet station operated for 15 years, under three sets of letters: first, “CC” for Cape Cod; then “MCC” for Marconi Cape Cod; and finally “WCC” when all eastern U.S. stations took the “W” prefix.

I’d like to think that this period gave South Wellfleet an opportunity to be less of a “backwater” and more importance as a place where a very modern activity was taking place. Marconi Station put a bit of a polish on South Wellfleet.

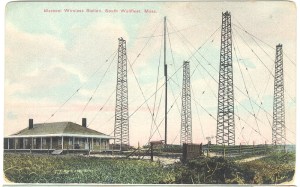

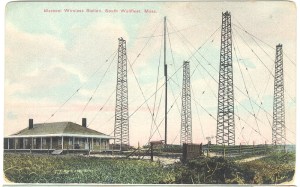

Color photo postcard of the Marconi site pub by Everett Nye

Each day in Boston the news dispatches and private messages were sent by telegraph to South Wellfleet where the station now had its own telegraph operator. By 10 PM, the wireless station had punched the messages into a paper tape, and the spark transmitter began a nightly operation. They repeated the program three times a night with 15 minute intervals between each transmission.

During these years, several Wellfleetians played significant roles in its operation. In the 1910 Federal Census, I found several people who worked there, and still others are mentioned in various accounts of the Marconi operation.

Harold Higgins, age 24, worked as rigger at the Wireless Station. Eva Higgins, his 23-year-old wife, is listed in many accounts as the cook and housekeeper for the Marconi staff, but the census taker did not note that. Perhaps she did not work there until later.

Mrs. Higgins, Marconi Cook

Higgins’ father-in-law, Melgar Pierce, is listed in some accounts as a rigger, as is Lewis Paine, who is 62 years in the 1910 census. Herbert Nickerson, age 34, born in Massachusetts, is an engineer at the Marconi Station, and has been married to his wife, Ethel, age 27, for one year. At the Marconi Station itself, Oscar Christianson, born 1884 in North Dakota, is the manager. Samuel Campbell, born 1882 in England to Irish parents, is a machinist. Richard Coffin, born 1885 and from New York, is an operator. John Simpson, born in 1884 in Ireland, is an operator. Adolph Brunner, a German born in 1885, was listed as a cook.

George Kemp, an Englishman who was mentioned in the previous article as Marconi’s chief assistant, met the Kemps of Wellfleet on his visits, but it’s not known if there was a direct relationship between the families.

Carl Taylor, the engineer mentioned above, settled in Wellfleet himself. In the 1920 census, he is living with his mother-in-law, Mary Tubman, and his wife, Mabel. Carl Taylor had come over to the Cape from England, and met Mabel at the station where she had

Marconi Station crew. Last man on right is Nickerson. Photo furnished by Walter Campbell

been a housekeeper helper. Mr. Taylor died in 1968, at age 93, having served as a Vice President of RCA Global Communications, retiring in 1941. He and his wife came back to Wellfleet during the summers. He kept up his local interest in the South Wellfleet station, as discussed below.

Samuel Campbell married Ethel Townsend of Wellfleet in 1914. His 1962 obituary listed him as a founding member in 1837 of the South Wellfleet Neighborhood Association. His son, Walter Campbell, was part of the 1963 dedication of the Marconi site in the Cape Cod National Seashore.

Everett Nye, the Wellfleet Postmaster, produced the postcard shown above. He must have been closely engaged with the Marconi event, as he also took the image on the card and had it made into a commemorative plate, sending it to England for manufacture and

Marconi Plate

importing it through Boston. The photo I was able to download is from a Christie’s auction.

Another important wireless station staff, Irving Vermilya, was the manager of the South Wellfleet station in 1914. As a boy, he was fortunate to meet Marconi and set his sights on a wireless career. When he was old enough, he became a wireless operator at sea, and then was chosen to manage the station. He wrote a piece later in life about those days, commenting on the need to have good food at the Station, and reminiscing about the days when World War I started, and the Navy moved in to protect the Station but forgot to put bullets in their guns.

Vermilya served at WCC Marconi Station during the War with the Station under the control of the U.S. Navy. In 1912, after the Titanic disaster, when the U.S. Government began to require that all wireless operators take a test and be licensed, he went to the Brooklyn Navy Yard immediately and became the first license issued. Later, he established one of the first radio stations serving the Cape, in New Bedford, and is still remembered today as a talented ham operator who helped promote amateur radio efforts throughout his career.

Another memory of the South Wellfleet Station came from Marguerite Barker of the fourth generation of the Barker family which I’ve written about previously. In a letter to The Cape Codder , she recalled visiting her grandfather, George W. Barker, in South Wellfleet.

Mrs. Higgins with the butcher wagon

Mr. Barker’s farmhouse still stands, just south of the Old Wharf. She remembers the summer vacations she spent in South Wellfleet, and then recalls:

…riding over the sand roads with Grandpa to deliver butter, eggs and garden crops to the several men stationed at the Wireless plant. The trip was never completed without a run down and up the big dunes at the back shore. There were no bathers or picnic parties in those days. At night we’d watch the many-colored flashes from the tall towers, indicating more messages being sent somewhere. The four huge steel towers were a landmark and could be seen from many miles around. From the Boston boat, long before the Provincetown shoreline was visible, the passengers could plainly see the four towers rising majestically. To me, they marked Grandpa’s town, dear old South Wellfleet.

Other South Wellfleet residents are remembered in accounts of the Station. Degna Marconi writes that “Billy” Hatch (William Hatch) was a local watchman for the Station who amused himself by playing a triangle and singing while keeping watch. This must have occurred in the early period when Marconi was still visiting. Marconi noticed Billy’s musical interest, and invited him to the station on one occasion — and played the piano while Hatch sang for him.

Degna Marconi mentions Eliza Doane as the woman who “patched and sewed and mothered the men” at the South Wellfleet Station. This would be the mother of Fred Doane written about in a recent post. The Higgins family who also helped lived closeby to her residence in the census documents, as was William Hatch. More than one account mentions Fred Bell as having a butcher wagon that would bring meat to the South Wellfleet Station.

A startling accident occurred in 1907 when the operator, Arthur Dakin, was found dead, electrocuted, in the operations room at the South Wellfleet station. Reports of the death concluded that he had been “experimenting” on his own.

When World War I broke out, the U.S. Navy moved to protect the wireless stations, and when the U.S. entered the War in 1917, the government actually seized the stations. Until February 1918 the U.S. Navy operated the Station, and then closed it and moved its operations to Marion, Mass., and, later, to a new station in Chatham. By the time this

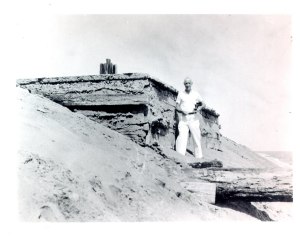

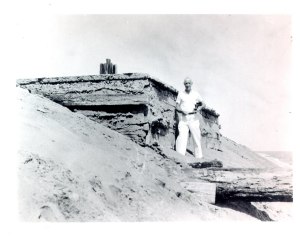

Remains of Marconi in 1941. Photo J.C. Hicks

decision was made, the erosion in South Wellfleet was apparent. The Navy disliked private operations, and, under its pressure, in late 1919, Marconi sold its American radio assets to the newly formed General Electric Corporation’s Radio Corporation of America. The operations at South Wellfleet were moved to Marion, Massachusetts.

The now abandoned South Wellfleet station fell into disrepair, and the loss of the dune

Tower base photo by Fred Parsons

during storms caused the towers to start falling down. I’ve posted photographs from the 1920s and 1940s which show the slow destruction. In the 1920s two Orleans contractors bought the plant from the government, salvaging the bricks and timber, trucked them to Orleans, and used them in cottage construction at Nauset Bluffs.

We also have today in South Wellfleet the “Wireless Road” that travels through the woods to LeCount Hollow Road. When you visit the Cedar Swamp in South Wellfleet, you will walk on a piece of that original road. The swamp is mentioned in the deed of the property.

Sam Campbell at site; photo by Walter Campbell

The U.S. Government kept the land and, after operating for some time as a Naval Station, the area became the U.S. Army’s Military Reservation Camp Wellfleet, a feature of South Wellfleet I’ll cover in a future blog. Eventually the land was folded into the Cape Cod National Seashore.

In 1938, as the South Wellfleet Neighborhood Association was organizing, The New York Times wrote about plans the group was pursuing to establish a memorial at the Marconi site. They were considering asking the federal government to establish parkland for such a site. World War II intervened, and in the late 1940s, additional newspaper accounts reported on the plans to memorialize the Marconi site. Marconi did not live to witness the War, as he died in 1937. But he did begin spending more time in his home country during the late 1920’s, and divorced and remarried during that time. His second wife was a much younger Italian woman, and Benito Mussolini was the

Marconi Towers tumbling down the dune. Possibly Fred Parsons photo

best man at his wedding. This was an unfortunate ending to Marconi’s career, joining the Italian fascists. Maybe this aspect of Marconi’s life made the U.S. Government less interested in the memorial.

In 1950 the South Wellfleet Neighborhood Association established a granite marker commemorating his work, and placed it at the Wireless Road/LeCount Hollow Road corner. (Today, this granite marker is at the National Park Marconi site, on the left side of the sidewalk as you enter the Interpretive Shelter.) Carl Taylor made a speech that day in 1950 remembering his old boss, and Samuel Campbell was on the Committee.

The Marconi site is a well-marked place within the Cape Cod National Seashore today. When the shelter structure was built near the remains of the Marconi site, Carl Taylor

1963 Marconi site dedication

attended the dedication, as did Samuel Campbell’s son. In 1969, the National Seashore named the nearby beach “Marconi Beach.” In 1974, a group of Italian businessmen, paid for a bust of Marconi to be added to the site. It was stolen in 1989, but recovered, and now is on display in the Headquarters Building near the site.

At some point, in the early 1960s, the daughter of the Higgins family mentioned above, Lyndell Higgins, served as the secretary to the Superintendent of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

This past year, as the 100th anniversary of the 1912 Titanic disaster was remembered, the Marconi site was given attention once again for the role wireless telegraphy played in helping bring the Carpathia to the sinking ocean liner to help save hundreds of passengers.

Sources

Marconi, Degna, My Father Marconi, on line at www.archive.org

Barnstable Patriot online archive: http://www.sturgislibrary.org

www.earlyradiohistory.us

Federal Censuses online at www.ancestry.com

The New York Times archive

Newspaper account on line at www.genealogybank.com

Cape Codder online at www.snowlibrary.org

Cape Cod National Seashore website

Photographs on the site: www.picassaweb.google.com/egcrowell6/wellfleetmarconipictures