This is the sixth post in a series about life on the Outer Cape during World War II

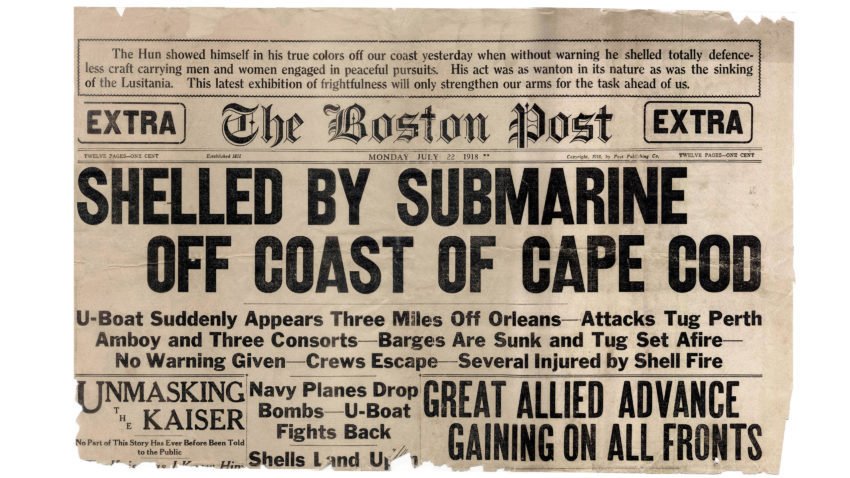

In June, in Provincetown, Arctic explorer Rear Admiral Donald MacMillan reminded Americans that the Germans could launch an attack on the U.S. using Greenland as a base. In April, the U.S. government had signed an agreement with Denmark’s government-in-exile establishing Greenland as a U.S. Protectorate for the duration of the war. In June, MacMillan was reactivated by the U.S. Navy to go to Greenland.

A young woman, a high school student in Provincetown, told her schoolmates about her family’s flight from France after the Nazi invasion. The family was now living with the grandmother in Provincetown.

In early July, after the 1200 men arrived in North Truro, the WPA Recreation Director in Provincetown set up a few days of activities for them, as local citizens learned to provide recreational events for military men. There was a baseball game, and a dance, with both radio and phonograph music, and the younger women “hostesses” being chaperoned by older women of the town.

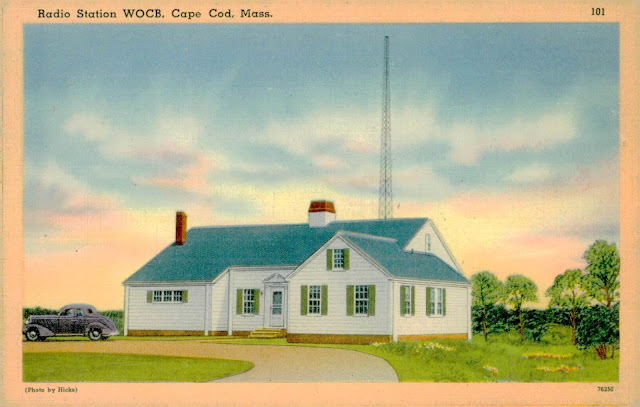

Also in June, Frank Shay, speaking on his radio show on WOCB, announced, “The people of Wellfleet have resolved themselves into a Committee of Public Safety, knowing that, if the mad dog of Europe in not overcome by Russio, or England, the Outer Cape will become the last coast of democracy and will have to be “defended by men, women, and children alike.”

During the spring and summer, the Cape raised funds for a “Flying Ambulance” for the RAF in England. They named it “The Cape Codder.” Before the plane was sent to England, it was flown around the Cape to various towns so that people could see it. During this time, many connections were made between Cape and English towns sharing the same name: Yarmouth, Falmouth, Truro, and the English Barnstaple with the Cape’s Barnstable.

In July, Admiral Turnbull of Provincetown was appointed Chair of the Provincetown Committee of Public Safety; by October, he would be leading the effort on the Outer Cape, overseeing the area from Provincetown to the Orleans town line. Trumbull is quoted as saying, “Fail to prepare, prepare to fail.” Civilian defense schools were set up in Hyannis and, later in the year, in Provincetown.

In early August, an Army training exercise appears to have affected the Brewster-Orleans area more than the Outer Cape. The Boston Herald reported on August 1 that 6600 troops from Camp Edwards would be staging a battle with one group playing the part of an invading Nazi army that had landed in the Brewster-Orleans area.

By late August, there was more Naval activity in Provincetown Harbor. The Provincetown Advocate reported, “The cruiser U.S.S. Tuscaloosa arrived last night and joined a large fleet of warships.” There was a dance for Naval personnel at the Town Hall. In October, the newspaper wrote, “Three of four destroyers of the new type and one submarine came in and anchored in Provincetown Harbor after dark last night and left again before it was really light in the morning.” A branch of Naval Intelligence opened in the Provincetown Post Office building, welcoming help from the public if anyone was observed interfering with Naval operations. In late October, the Navy constructed a steel docking float to “facilitate the landing” of officers and sailors.

In August, the U.S. Navy conducted “defense tests” at the Provincetown airport near the Race Point Coast Guard Station. They sought permission from the town to erect a temporary mooring mast for blimps that would “work with submarines in local water.” Twenty men and their officers were stationed there for three weeks.

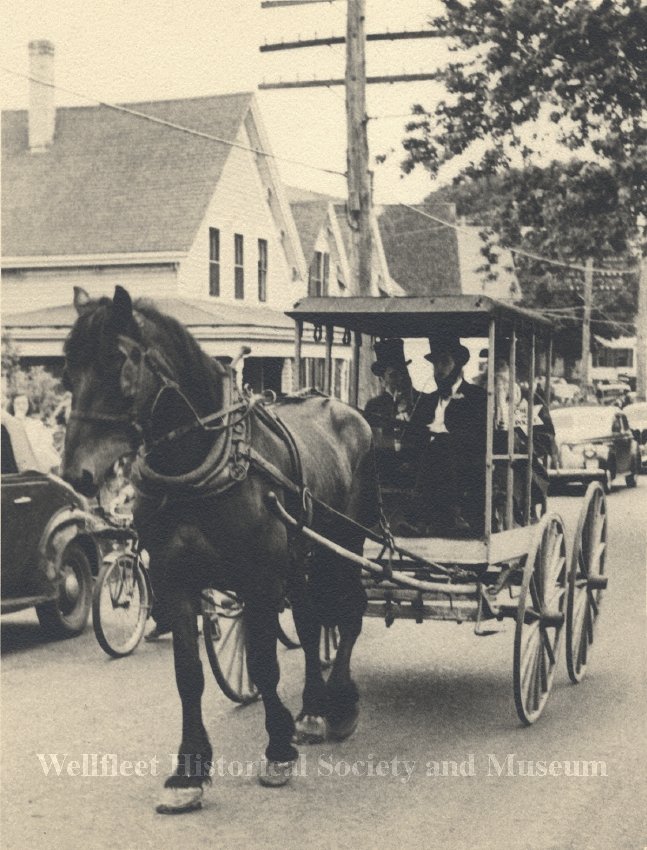

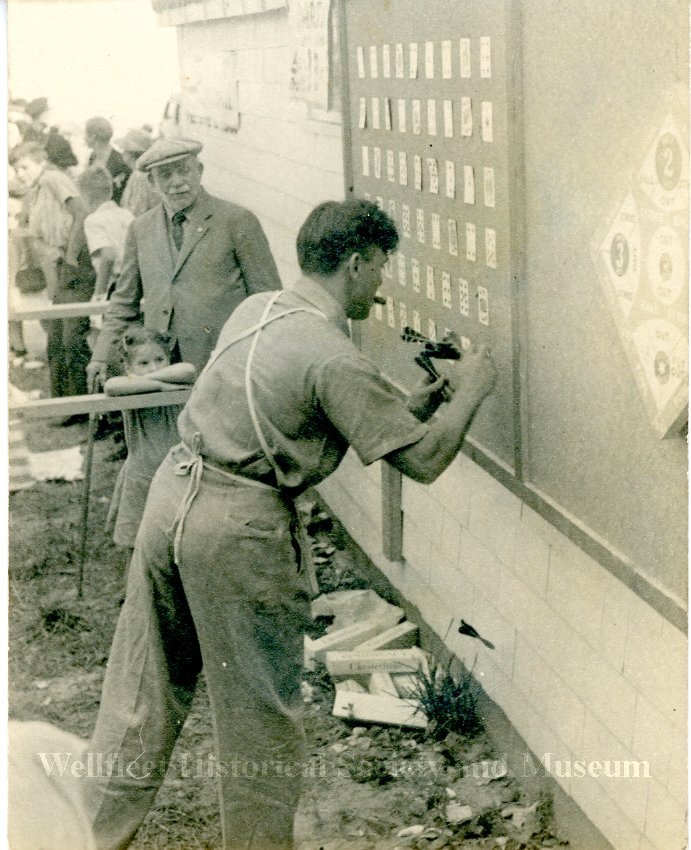

Not all events were military. Wellfleet’s second Town Fair was held on August 23, under the direction of Frank Shay and a hard-working committee. The crowd was a bit smaller. Funds were raised for the Colonial Hall, the High School’s Washington, DC trip, the Lower Cape Ambulance, and a new fund for the Wellfleet Fire Department. Many prizes were awarded for poultry, handicrafts, baked goods, vegetables, fruits, and flowers; canned and preserved foods; clam chowder; and quahog pie.

There were very few crime reports in the Cape Cod newspapers, perhaps because tourism was so important. However, in the summer and fall of 1941, these stood out: the Truro Town Clerk, who also served as the Treasurer and Tax Collector, was tried and convicted for stealing the town’s funds, and the Provincetown Police Chief was indicted for covering up a crime in 1938. Also in Provincetown, two crimes, one involving strip-tease dancers at an event, and the other a New York City man arrested for “lewd, wanton, and lascivious behavior in the company of two sailors in a car behind Town Hall.”

A speaker at the Provincetown committee in October would push hard for the efforts to organize, since all citizens of Massachusetts would be expected to perform the duties assigned to them. During the summer, Turnbull explained that citizens who were already professionally trained in the duties required for civilian defense, such as firefighting and first aid, would be asked to serve and, if they refused, and no one else volunteered, they could be “drafted.”

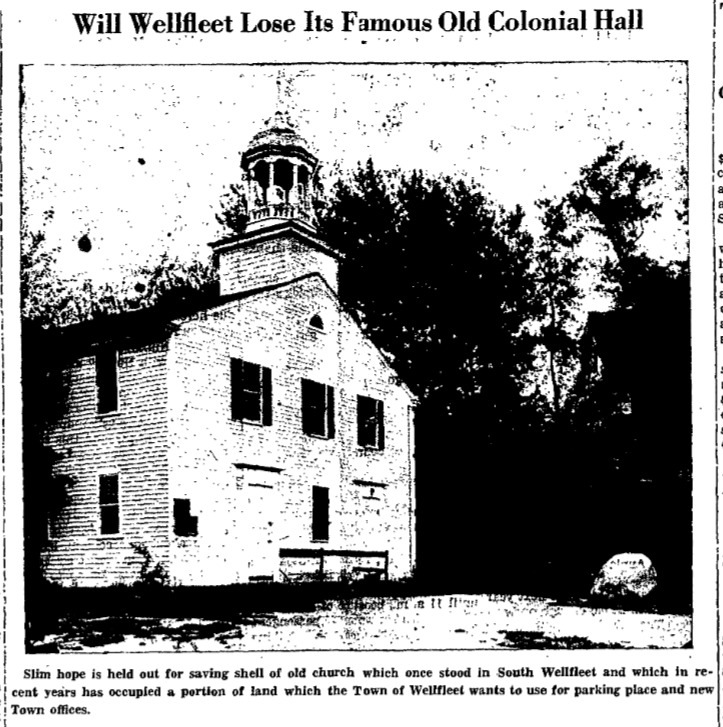

At a Special Town meeting in Wellfleet in September, the agenda included some property transfers, including one in which the Methodist Church gave the land under the fire station to the town. There were a few more expenses to finish the Colonial Hall, including painting and installing plumbing. Another item concerned building a road through the South Wellfleet Cemetery. The Town Offices were relocated by November, as town officials moved from their “cramped and dusty offices over the library.”

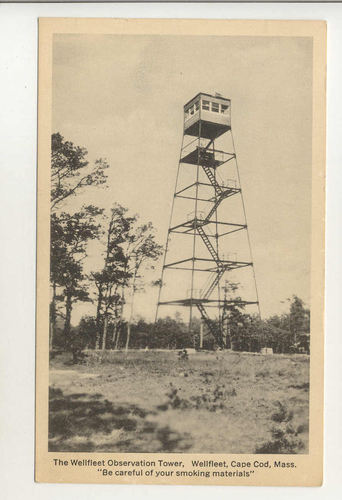

On October 10th, the Army staged an “imaginary bombing” as a test for the fifteen Cape Cod towns to test their ability to handle an air raid. Admiral Turnbull, now in charge of the Outer Cape from Eastham to Provincetown, handled a telephone system connecting the towns. The Legionnaires who were part of the AWS watch posts reported their identification of all the planes to their report center.

A few days later, Turnbull discussed making a plan to use all of the Provincetown fishing boats to evacuate women and children from the town “in case there is a serious fire from incendiary bombs.”

Civilian defense organizing in Wellfleet during the summer of 1941 was taking place. There was a training course for both Wellfleet and Truro volunteers, taught by Mr. Beebe at Truro’s Odd Fellows Hall. Training courses were also underway in Hyannis. Wellfleet must have organized, because Charles Frazier mentioned “a corps of workers” who were commended by area officials for their alertness and efficiency during an October exercise, which would have been the air raid testing event described above. At a late October meeting of the Board of Trade, Frazier said that everyone in Wellfleet had received a form letter asking them to indicate their role in the town’s civilian defense. He encouraged the Board of Trade to support the efforts.

Lawrence Gardinier, who had been serving as the town’s Police Chief for most of the year, was the Chief Air Raid Warden. He reported that the town would soon be showing a film of an actual air raid and the methods local officials used to save lives. He organized a meeting in Colonial Hall/Town Hall and appointed eleven deputies, one for each section of the town.

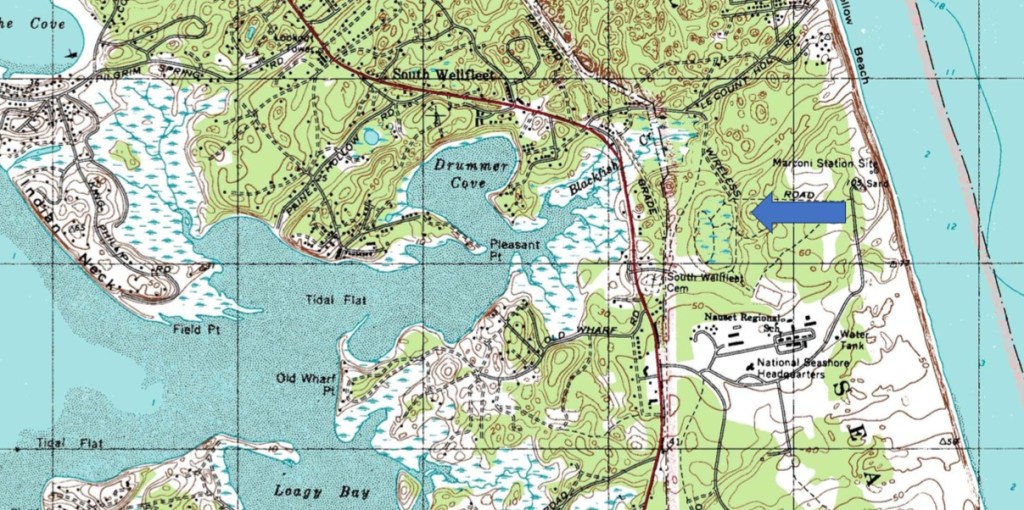

The meeting covered other topics. Dr. Oliver Austin Sr., in charge of the Ornithological Station in South Wellfleet, gave a presentation about the birds studied there and affirmed that the Station was not against game bird hunting.

On October 31, 1941, the U.S. Destroyer Reuben James was torpedoed and sunk off the west coast of Ireland while escorting a convoy, with the loss of 115 seamen and officers. It was not the first U.S. ship to be torpedoed, but it was the first one lost. Provincetown’s Turnbull had commissioned the ship when he was an active Naval officer. Woody Guthrie made the event famous with his song, “Tell me what were their names? Did you have a friend on the Reuben James?”

A soldier from the 2nd Army Aircraft Warning Company fell from an Army truck and died in Truro. His name was William Faulkner.

In November, the U.S. Coast Guard was transferred from the Treasury Department to the U.S. Navy “as required by law.” That month, the Coast Guard began registering every person who worked on boats, wharves, and docks, even fish truck drivers.

A new course was offered at the Hyannis Civilian Defense training school: “Recreational Defense Training,” to help citizens learn how to handle recreational events involving soldiers in their midst.

In November, Wellfleet announced a Muster Day under the auspices of the Wellfleet Committee of Public Safety, where every man, woman, and child would report for civil defense duty. On that day, air-raid films would be shown at 3:30 pm for students and again at 8 pm for other Wellfleet citizens. Civil Defense Captains would explain their work. At the evening meeting, Mr. Frazier, the General Chair of Wellfleet’s Defense Program, introduced others playing a role in managing the town’s program. The bank president, Cyril Downs, was in charge of planning; his wife was in charge of the women’s division; Frank Shay was in charge of public relations; and Stacy Taylor was in charge of supplies.

A speaker from the State’s Committee on Public Safety spoke about the importance of citizens participating and getting trained so that they would not be fearful in an emergency. The speaker went on to announce that the military had already scheduled a blackout of the entire Atlantic seaboard to 300 miles inland, and that Cape Cod citizens would need to learn how to operate under blackout conditions.

December 7 arrived. I did not find any published information on how the Outer Cape residents responded to the Sunday afternoon news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The first Cape Codder to be killed in the war was Private Robert S. “Scotty” Brown of Chatham, killed at Hickson Field, Pearl Harbor. His mother got a telegram from the War Department. The Barnstable Patriot listed the other men serving in the “war zone.”

The Provincetown Advocate had recently published a report of Provincetown native Lt. Commander Clarence M. Bowley, who was stationed at Pearl Harbor and was awaiting news. Admiral Bowley lasted through the war, received the Navy Cross for a battle in Okinawa, and was laid to rest in 1988 in the National Cemetery in Bourne.

The Barnstable Patriot announced the appointment of Admiral Chester Nimitz as the Commander of the Pacific Fleet, and wrote about his connection, through his wife, Catherine Freeman, to Wellfleet’s Freeman family, and his frequent visits to the town. Her sister, Elizabeth, lived there still, on Money Hill.