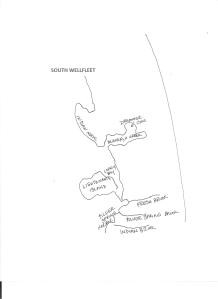

Land Distribution in South Wellfleet

Since I began researching the history of South Wellfleet, I’ve looked for evidence of the earliest European settlers — and evidence of native people populating the area, yet another topic. This article discusses the records I’ve found of land distribution known to be in South Wellfleet.

In Durand Echeverria’s book on the settlement and political development of the town of Wellfleet, A History of Billingsgate, he refers to land deeds that named the area just to the north of Indian Brook “hither Billingsgate.” Indian Brook, now called Hatch’s Creek, remains the dividing line between Eastham and Wellfleet. “Hither Billingsgate” is another earlier name for South Wellfleet.

The three Barnstable County historians Pratt (1844), Freeman (1858), and Deyo (1890) touch lightly on early settlers but do not provide many details. A more certain early record is the 1734 notation in “The Records of Wellfleet, Formerly the North Precinct of Eastham, Massachusetts” published in The Mayflower Descendant. It names the men who wanted to remain with the church in Eastham, and pay their taxes there rather than to the new “precinct” of Billingsgate. Presumably, they lived with their families in South Wellfleet, and the meeting house on Chequesset Neck (in today’s Wellfleet) was too distant.

Wellfleet, and the meeting house on Chequesset Neck (in today’s Wellfleet) was too distant.

There are two other records that we can draw certainty from — both are land distribution lists. The first is the published records of land distributed by the Town of Eastham, although there is no record of home building. Another is a record of the 1711-1715 distribution of Eastham land that had been held in common. Taken together, these records, as well as many family histories, are my sources for who was living in today’s South Wellfleet. Another source, one that I have not fully explored, is the record left by individual’s wills, where land is left to family members and others by the deceased.

The Town Records of Eastham, newly published by Jeremy Dupertuise Bangs, lists the earliest land grants by the ruling town of Eastham, in places that named South Wellfleet sites:

- 1654, a meadow at Blackfish Creek to Richard Bishop, next to the meadow of William Twining

- 1658, half acre of meadowland at Blackfish Creek transferred to Mr. Smalley by Daniel Cole, next to that of Richard Sparrow.

Then, in 1659, there are numerous land grants in Billingsgate, many on the islands west of the harbor where historians have determined that the settlement of Wellfleet began. In South Wellfleet, these 1659 land grants included 3¾ acres of meadow to Jonathan Sparrow and the same amount to William Walker, at Silver Spring Meadow, on both sides of Silver Spring Creek. There’s an important distinction made in these land distributions: “meadow” refers to the marshland where salt hay could be harvested for the animals that were key to the farms of the early settlers; I plan to post about salt hay making in a separate article. Many of the distributions around Blackfish Creek were such meadow grants.

In 1662, Lt. Joseph Rogers received two acres on “the netherside” of Little Blackfish, as Blackfish Creek was sometimes called, between land belonging to Job Cole and John Doane. Rogers was an important town figure, named the head of the Eastham militia soon after the town began, at a time when Plymouth Colony took action to be ready for potential disruption from the Dutch in New Amsterdam. Fort Hill in Eastham was so named because it was the site of the fort that Plymouth Colony had ordered the town to build at that time. In 1665, Joseph Rogers Jr. was given four acres “at Loge,” today’s Loagy Bay, adjacent to land belonging to Samuel Freeman. There’s no record I’ve found to tell us why Loagy Bay is so named; I wonder if it might reflect the word “logy,” an old Dutch term meaning slow-moving and sluggish, perhaps referring to the movement of the tides.

In 1664 and 1665 there was another round of land distribution. Jonathan Higgins, son of Richard Higgins, received three acres of meadowland at Silver Spring, adjacent to the land of Mark Snow, son of Nicholas Snow. When Richard Higgins and Nicholas Snow became Eastham Proprietors, they were older and it wasn’t long before their sons needed land as they married and started their own families.

In 1665, Nicholas Snow was given five acres at the mouth of Blackfish Creek and, later that same year, two acres of meadow “in the second meadow coming out of Blackfish Creek.” The second piece was land transferred from Mr. Doane, extending to land belonging to Job Cole. In 1678 Nicholas Snow was given an acre and a half “with the sedge within land belonging to William Walker against the Silver Spring Creek.”

In his will of 1676, Nicholas left to his son, Jabez Snow, “one-half of a meadow at Silver Springs on the northside of William Walker, and the cliff of upland adjacent to the meadow and all the sedge ground about it (next) to Ephraim Doane’s.” Jabez Snow was the grandfather of the Sylvanus Snow mentioned later in this piece. Nicholas Snow’s son, Joseph Snow, who died in 1722/23, left to his son, Benjamin, “1/4 meadow on the south side of Lieutenant Island” and to his sons, Stephen and James, meadow and upland at Silver Spring.

The Snow family figures prominently in the early days of South Wellfleet. Previous to the establishment of Wellfleet as a town, there were years of negotiations as Billingsgate — the north part of Eastham — began its separation. In 1723, when the Billingsgate residents were given permission to have their own minister, the area so-designated was as far south as Blackfish Creek, leaving those further south in South Wellfleet able to still attend church at the Eastham meeting house.

In 1734, when Billingsgate was set aside formally as “the North Precinct” it was Sylvanus Snow and “five others” who were released from paying their tax to the precinct, presumably because they were living closer to the Eastham church. The others were Eldad and Ebenezer Atwood, Joseph and Jesse Brown, and Samuel Snow (Sylvanus’ brother). These records are the first we have of actual South Wellfleet settlers who did not want to travel all the way to the new meeting house at Chequesset Neck. Sylvanus Snow’s mother, Elizabeth, is buried in the cemetery now called “Bridge Road Cemetery” in Eastham, where the second Eastham Meetinghouse stood, further proof that the Snows of South Wellfleet attended church in nearby Eastham.

When the limits of Wellfleet were described in 1763, Wellfleet was “joined from the Bay to the Back Side Sea” but “leaving aside the estate of Sylvanus Snow as excepted in the incorporation.” In the 1802 description of Wellfleet’s ocean side by the Humane Society, telling seamen where they could find shelter after they scaled the dunes, there was a hollow described as Snow’s Hollow, two miles south of Cahoon’s, noting that the County Road rounding the head of Blackfish Creek was a half-mile west. However, on the 1858 map, Snow’s Hollow is prominently designated further south, close to the Eastham border, just east of Fresh Brook. Today that hollow is not named, since there is no beach access for 21st-century swimmers. The more northerly hollow, north of the National Park’s Marconi Beach, is now LeCount’s Hollow, named for the family that settled nearby at a later time.

Returning to the seventeenth century, in 1664, Governor Bradford got twelve acres of upland and 44 acres of meadow near Lieutenant’s Island “now lawfully possessed by Richard Higgins.” Governor Bradford never settled on the Cape; perhaps the land was for payment of a debt. That same year, Jonathan Sparrow, son of Richard Sparrow, an original Proprietor, gave Richard Higgins an acre and a half of meadow at Indian Brook, between land belonging to Nathaniel Mayo and Daniel Cole. He also sold three and ¾ acres of meadow on both sides of Silver Spring Brook, nearby to land belonging to William Walker. Also in the mid-1660s, Edward Bangs, Josiah Cook, Robert Wixam, and John Jenkins each received two-acre meadows on the Blackfish River, another name for Blackfish Creek in early deeds.

Richard Higgins, a tailor and one of the Eastham Proprietors, left the Cape in 1669, to purchase and settle on land in Piscataway, New Jersey. His son Benjamin, already grown and married, stayed in Wellfleet, and was grandfather to the Thomas Higgins who built the first part of the “Atwood Higgins House” on Bound Brook.

When Edward Bangs wrote his will in 1676, he left four acres of meadow at Blackfish Creek to a third son, Joshua, along with other extensive land holdings. When Lt. Joshua Bangs died in 1706, his own son Edward had already died, so he left his meadow near Blackfish Creek to John Knowles. Previously, when I was researching Old Wharf Point, I noticed that the Knowles family still owned a piece of land near there in the 19th century.

In 1666/67 Daniel Cole received four acres on the southerly side of Indian Brook, “beginning at the cartway that goes over the bridge.”

In 1669, Captain Samuel Freeman got four acres of meadowland at Loge (also known as Loagy Bay), near the north arm of Silver Spring Creek. We know that Captain Freeman had a family tie to Governor Bradford’s wife.

In 1672, William Brown (recorded as Browne) of Sandwich received 16 acres and “associated meadow” at Little Billlingsgate and Silver Spring in a sale from a Daniel Seward. Mr. Browne was the great grandfather of Joseph and Jesse Brown, who were also released from North Precinct taxes along with Sylvanus Snow, presumably because they also lived in South Wellfleet, so this deed notes their family’s beginnings in South Wellfleet.

James Brown, Jesse and Joseph’s father, was another who left South Wellfleet. He moved to Gorham (then part of Massachusetts, now in Maine) in about 1750, as did some of the Harding family members who had become South Wellfleet settlers. Land grants were made in Gorham in 1733 to reward the men who had successfully fought the Narragansetts in King Philip’s War of 1675. By the time the grants were made, the land was given to children and grandchildren of the soldiers. Other members of the Brown family stayed in South Wellfleet. George Brown married a daughter of the Freeman family, mentioned above, and lived to 1767; he is buried in Duck Creek Cemetery.

Another family named in the agreement of 1734 concerning the payment of North Precinct taxes was Ebenezer and Eldad Atwood. Since so many of these early Eastham families have been researched, it’s pretty easy to check on who the early settlers were. Stephen Atwood was an early arrival in Eastham, producing the large family characteristic of that era. His son, Eldad, married a Snow daughter. They had numerous children, including Eldad, born in 1695, and Ebenezer, born in 1696. Other Atwood children settled in Wellfleet’s western islands. The Eldad and Ebenezer named in the 1734 town meeting notes appear to be the two who were living in what was South Wellfleet. Children born later in the 1700s married daughters of families I can place in South Wellfleet also — Witherell, Cole, and Doane. One of my early blog postings was about the Barker family; their son married Lizzie Atwood, whose family line can be traced back to these South Wellfleet Atwoods.

The second source for land distribution records, mentioned above, is the Division of 1711-1715. This record has been published separately, and I found a copy at the New York Public Library. It’s a list of names, numbered from 1 to 143, of “Lot” and “Woodlot” distributions. There was no key to the list, although I found a note in yet another source that it was numbered from south to north, but with no indication which numbers were in Wellfleet. Fortunately, Durand Echeverria dug a bit deeper than I have been able to do, and noted several of the Wellfleet grants made at this time, including some in South Wellfleet, allowing me to assign numbers to sites. Again, this list refers only to land, not homesteads:

- Brown family members: lots 111, 115, 117, 119, 120, 121, 123.

- Harding family: 112 and 113. In her research, Polly Stubbs, noted that John Witherell bought his land from the Hardings when they moved to Gorham, one of the families receiving land grants there. Durand Echeverria noted that this Harding land was on Blackfish Creek. (I wrote about Major John Witherell several blog posts ago.)

- Isaac Doane lot 118 which Echeverria notes was on Indian Brook.

- Isaac Pepper received lots 104 and 107; I have a record of a 19th century Arey land naming a portion “the Pepper marsh” perhaps referencing this 18th century land.

- William Walker received ½ of lot 104, sharing this with Isaac Pepper; a John Walker got lot 116.

- Isaac Higgins got Lot 114.

- The Collins men – Jonathan, Joseph Sr., Joseph Jr. and John — received lots 101, 102, 103, and 110.

- Daniel Atwood received lot 108.

- Joshua Cooke received 109.

- Stephen Snow received Lot 106.

This ends my research that identifies the earliest South Wellfleet families.

Sources

Durand Echevierra, A History of Billingsgate, Wellfleet Historical Society, 1991.

Kneedler-Schad, Lynn, Katharine Lacy, Larry Lowenthal, Cultural Landscape Report for Fort Hill, Cape Cod National Seashore, 1995

Jeremy Dupertus Bangs, editor, The Town Records of Eastham During the Time of Plymouth Colony 1620- 1692, (Publication of the Leiden American Pilgrim Museum, 2012)

Trayser, Donald G. “Eastham Massachusetts 1651-1951” Eastham Tercentenary Committee, 1951

New England Historical and Genealogical Society, on-line publication of The Mayflower Descendant.

Smith, Edward Leodore, compiled in 1913, Ancient Eastham, Massachusetts, two lists of those proprietors there in seventeen hundred and fifteen: from the originals in Town Book Lands and Ways, 1711-1747.

David Kew’s Cape Cod History site: www.capecodhistory.us.