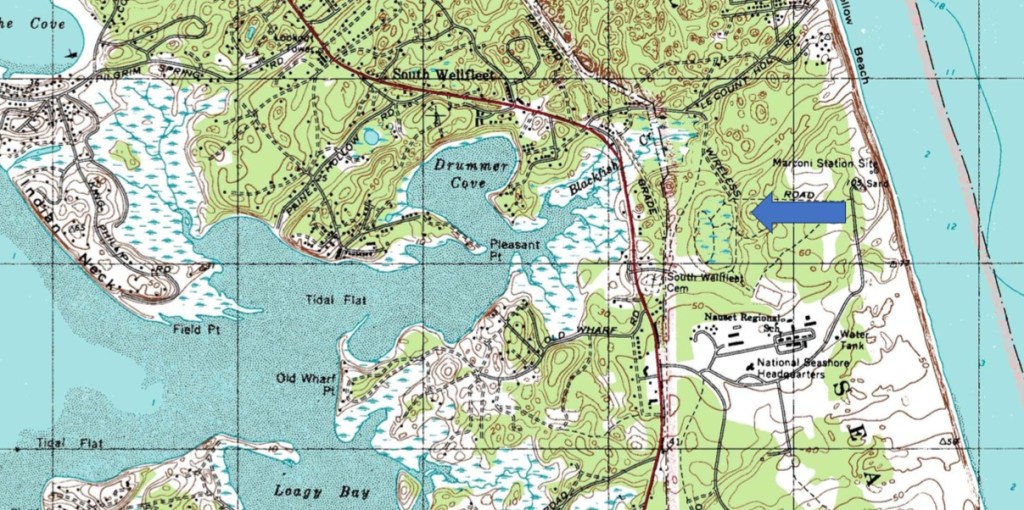

The Atlantic White Cedar Swamp (Chamaecyparis thyoides) within the Cape Cod National Seashore (CCNS) is popular with park visitors. While accessing the walk involves driving out to the parking area for Marconi Beach, the swamp and its boardwalk trail are relatively inland, not far beyond the Rail Trail as it winds through South Wellfleet. On a map, the swamp is just to the north and west of the South Wellfleet Cemetery.

The CCNS brochure describes how the cedar swamp was formed. Glaciers left a depression in the land; as the ocean rose, the freshwater table of land was lifted, and a “kettle pond” developed about 7,000 years ago. Some 5,000 years ago, Atlantic White Cedar began to grow in the depression, as it did in numerous areas around the Cape and southeastern Massachusetts. Today’s plant debris in the swamp makes a peat layer of 24 feet.

A few years ago, I heard from a neighbor that one of the National Park’s outstanding volunteers, Rusty Moore, had done some work researching the owners of the Atlantic White Cedar Swamp. Since this is a South Wellfleet landscape feature, it caught my interest. Recently, thanks to Bill Burke, the park’s Cultural Resources Program Manager and Historian, I received the materials Rusty left in a file at the Seashore offices.

As I reviewed Rusty’s materials and then did my research, I found myself following what may have been his thought process. Beyond the research on the swamp owners, which was discovered only by reading multiple deeds at the Barnstable County Registry of Deeds, there was a question: How was the cedar used as a resource?

The books and other documents typically used for Cape Cod history provide scant evidence of the use of cedar by the Cape’s settlers in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Other natural resources are fully covered: whales, fish, shellfish, salt hay, cranberries, and salt-making.

The forests that were a resource for the Cape’s settlers were decimated by the early to mid-1700s. Cedar would have been one of the resources destroyed. According to a contemporary description, growing a new tree takes up to 50 years. According to the Seashore’s brochure, the original Cape builders used cedar for their farm buildings, for joists, frames, doors, rafters, floors, and for tanks to hold whale oil. They made fence posts to mark their property and to contain their cattle and sheep.

In his 1939 study of Cape Cod’s forests, Alpeter notes that when the Pilgrims landed, 97% of the land surface of Cape Cod was covered in forest. The principal tree species were white pine, hemlock, pitch pine, red and white oak, white ash, yellow birch, beech, red maple, tupelo, sassafras, and holly. He notes, “Great stands of coast white cedar (his term) occupied the bogs.” In 250 years, all of this forest was eliminated through systematic burning, clear-cutting, excessive pasturing, and insects and fungi attacks.

Wood was a fuel source, and it was used for home building and ship building. Initially, salt was made by boiling seawater, and the fires were made by burning wood. Wood fires also supported the try-works where whale oil was processed. Cedar might have been used in the building of salt works in the late 18th and early 19th century; a 1992 newspaper article about dredging at Rock Harbor mentioned cedar pilings “that might have been related to saltworks construction.”

Rusty’s file included neatly typed quotations from three writers in the 19th century who observed the lack of trees on the Cape. Timothy Dwight, the President of Yale College, wrote about the eastern United States in the 1790s, covering the outer Cape in 1800. He noted that, from Orleans, there was no forest until he reached a point one mile south of Wellfleet line. From this point to Wellfleet Village was a stand “lower and leaner than any we had seen before.” Dwight was followed by Edward A Kendall who wrote about his travels in the northeastern states in 1809, covering North Eastham and South Wellfleet. Finally, Rusty included Henry David Thoreau’s writing about the lack of good-sized trees on his walk in 1849.

Altpeter also discovered that, shortly after 1706, the Reverend Samuel Osborn of Eastham began teaching local inhabitants to use peat for fuel, “proving that 65 years had been sufficient for the people of Eastham to complete the destruction of their forest.”

Another item in Rusty’s papers was a copy of a letter from Mary Magenau, whose home was near the South Wellfleet Cedar Swamp. Mrs. Magenau wrote to the University of Massachusetts Forestry Department concerning information she had promised them about uses of the cedar swamp, based on her review of deeds that mention the swamp. She cites references to uses of the peat in the cedar swamp as possibly to enrich garden land due to the very poor soil in Wellfleet. But might it be possible that the harvesting of peat was for fuel?

The 1839 deed transferring a portion of the swamp from Timothy Cole of Eastham to George and Timothy Ward of Wellfleet reserves Mr. Cole’s right to “get peat” in the three winter months. This may be noting a use of the peat for fuel, not for enriching soil.

A search for Atlantic White Cedar in the pages of The Barnstable Patriot in the 19th century found plenty of mentions of cedar swamps all over the Cape. Most mentions were part of land sales descriptions, and several noted the conversion of a cedar swamp into a cranberry bog, a popular habit of the time. I found only one noting the actual use of the cedar trees.

An article in 1847 noted that Mr. Lovell of Yarmouth had covered a cedar swamp with beach sand to create a cranberry bog.

In 1888, it was reported that three gentlemen purchased four acres of cedar swamp in West Harwich to make into cranberry land. Also in 1888, Mr. Nickerson of South Orleans engaged a force of men clearing up a cedar swamp for cranberry culture.

In 1891, Mr. Phinney of Barnstable advised farm management, recommending that farmers “ditch the swamp and drain it, and turn it into a hay crop.”

In 1892, Mr. Frank Crocker of Hyannis received six horses from Boston to be used in draining the great cedar swamp “over east.”

In 1903, in one of the few mentions of cedar’s usefulness, Centerville’s Mr. Guyer “had a gang of men in the cedar swamp last week cutting and stripping poles to be used by the new Telephone Company.”

Finally, Rusty’s file included a page of a sketch of the cedar swamp land that he annotated with notes about owners. South Wellfleet neighbors shared the ownership: Timothy and George Ward, William Hatch, David Wiley, John Witherell, Noah Doane, and Ephraim Stubbs. Elbridge and Oliver Arey, sons of the second Reuben Arey, were left portions of the swamp in their father’s will. (As I worked on this project I discovered that Timothy Ward sold his home to William Hatch, which is the house that burned to the ground in 1939 that I wrote about here.)

Perhaps the number of owners helped “save” the swamp from being turned into a cranberry bog that a single owner might have pursued.

Rusty used a sketch of the swamp that was part of what appears to be a report on samples taken from the swamp. I may have identified this sheet as coming from a multi-university study of climate change. The study used samples from Atlantic White Cedar tree rings from 20 swamps to reconstruct temperatures in New England using radiocarbon measuring.

Another piece of paper in Rusty’s file was the 1850 “manufacturing census” part of the federal census, listing the men of Wellfleet who owned businesses. The first eight were carpenters, with George Ward, one of the cedar swamp owners, having the most extensive operation. While the others employed one man, he employed four and produced eight buildings yearly. This is the only link I found of an owner who may have been using the cedar.

That ended Rusty Moore’s papers and my exploration of Atlantic White Cedar in South Wellfleet.

In recent years, the Wampanoags have shared their use of cedar to build the frames of their traditional homes called wetus. My contact at the Truro Historical Society, where a wetu was recently built at the Highland House museum, thought that the source of that cedar was from Connecticut. There’s also a wetu at the Atwood Museum in Chatham. It’s easy to imagine the cedar from South Wellfleet serving this purpose.

Robert Finch recorded his essay about South Wellfleet’s White Cedar Swamp in his weekly “In This Place, A Cape Cod Notebook” in 2014. He found the White Cedar Swamp “magical and full of wordless meaning … a deeply mythic place, encompassing a watery underworld, a silent and muffled Middle Earth, with glimpses of a celestial overworld.”

SOURCES

This is a link to the tree-ring study: web.whoi.edu/coastal-group/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2020/12/Pearl-2020-A-late-Holocene-subfossil-Atlantic-white-cedar-tree-ring-chronology-from-the-northeastern-United-States.pdf

Altpeter, L. Stanford “A History of the Forests of Cape Cod” un-published 1939 M.S. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. npshistory.com/publications/caco/forest-history.pdf

Finch, Robert’s broadcast of his walk through the Atlantic White Cedar Swamp: Wellfleet’s White Cedar Swamp: A Walk Through the Brain of Nature | CAI

1850 Manufacturer Census for Wellfleet available at www.ancestry.com

Deeds for Barnstable County are available here: Barnstable County Registry of Deeds

Cape Cod National Seashore brochure “Atlantic White Cedar Swamp Trail,” undated